The present diptych titled Year Zero, Year One is from a major collection of works by Aydin Aghdashloo called Memories of Destruction. The Significance of this collection led to major sales at the Third Tehran Auction (2014), Bonham’s Auction in London (Islamic and Indian Art, April 2014), and Christie’s Dubai Auction (Modern and Contemporary Arab, Iranian, and Turkish Art, 2011). Inspired by the art of the Renaissance period and his curiosity about ambiguous aspects of the art history, Aghdashloo began creating the Memories of Destruction in the early 1970s. “Memories of Destruction began in 1974 with disfigured paintings of the Renaissance period”, recalls Aghdashloo, “I chose European Paintings of the 15th and 16th centuries as models. I did not wait to see the values of our times being destroyed. Instead, I began portraying memories of destruction, signifying original values that no longer existed in our times, and pointing to a period that knew no limits to outrageous demolition as well as to the fuggy air, the breathing of which would cause any angel to perish and turn to ashes. It reminds us of a scene in Federico Fellini’s Roma where mural paintings on the ancient walls would fade once they came in contact with poisonous air.”[1]

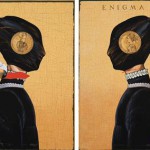

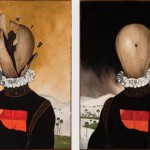

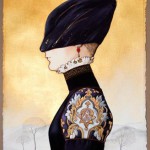

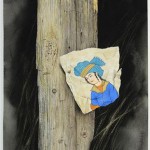

This collection is based upon a contrast between perfectionism and annihilation. The result is a visual paradox that brings forth allusions beyond it. A figure is seen in each picture that despite being sumptuous, has a wooden head. On the one hand, they bring to mind the dignity of imposing figures of the Renaissance period; on the other, they represent the sudden decadence of a significant being. Writings at the bottom of the painting indicate that in addition to merging textual and visual symbols, Aghdashloo challenges time, leaving spectators with ambiguities about history that are intertwined with the identity of the work. Usual elements of Aghdashloo’s painting are evident in this work; a Renaissance atmosphere, a surrealist skull made of old solid wood, a background that is reminiscent of landscape paintings of northern Europe or Flanders, and a highly elaborate drawing of clothes and a word that is trying to stir the conscience of human beings. In fact, Anno – or Anno Domini – in Christianity indicates the year of the birth of Jesus.

What Aghdashloo depicts is neither a portrait nor its destruction, but the “painting” itself, as an invaluable heritage that is an “insignia” of a civilization. In fact, he does not paint a Renaissance or Safavid figure; rather, he re-paints a classical western or Iranian painting. The act of painting to Aghdashloo is akin to a behavior or gesture that comes as a destructive act, targeting the picture by accurately drawing it to turn it into a tragic conceptual expression. Beyond the portraits and pictures, this is the symbolic treatment by Aghdashloo that brings us closer to the main concept of the work. He does not seek to abide by the principles of Modernism in painting. Therefore, what makes someone who looks at a painting from a Postmodernist perspective across a large span of time, to remain absolutely faithful to technique and take pains to paint? Aghdashloo is so mesmerized by a past golden age that he merely takes it upon himself to pay tribute to it. His narration of a classical age is neither symbolic nor formalist; it is rather a reflection of astonishment and bewitchment. His painting is enthralled by the magical excellence of the past. He admits that he is not delighted by his technical skills. So what remains is a refinement and meditation that he accomplishes through painting, as well as other incentives that are connected to his grievances of the times which is explicable through his rebellious and aggressive behavior.

In such a worldview, a painter is immersed in an infinite world of visual capacities of art history. He drags the audience to this visual paradox to create moments and destroy them in a trice.

[1] Aghdashloo, Aydin, Preface to the Collection of Paintings, Art Education, Winter 2002, Vol. 2, P.45